Metaphysician, Heal Thyself

May 15, 2014

Immediately, my work was about communicating. It wasn’t beautiful. I wanted,

without knowing, to develop new skills for communicating within my work. When

I gained access to metals and wood, I tried, for the first time, to make interactive

sculpture. The goal was the same: to communicate the ineffable. My tactic, however,

had shifted from showing the ineffable to trying to put the viewer in a position to

experience a metaphorical version of the feeling. For example, to simulate the feeling

of moments of clarity punctuating an otherwise muddled mind, I built a tall enclosure

for the head that allowed sight from small holes in the steel cylinder. I wasn’t satisfied

by these experiments, but my interest in communication was evolving.

When I began as a student at Purchase, I picked up at this metaphorically

communicative phase. I made video work that communicated real thoughts and experiences

through metaphorical actions. For example, I was interested in finding the end of my capacities

in the mode of Marina Abromovic, discovering which would fail first between my body

and my will. An early exploration of this idea was a video called Busy in which I picked an

arbitrary stand in for ‘activity’ by filling a tub with water and punching the surface repeatedly

presumably until I couldn’t. I looked at work like Mel Chin’s SAFEHOUSE (2008-2010) as

examples of metaphorical action that spoke about concrete events. Finally, I took a course that

bridged the gap between lived experience and communication. It was called Social Sculpture,

and in it I learned that one could create real experiences as a form of communication, without a

metaphor or image to mediate.

From there, I began to experiment with putting people in simulated situations to evoke

tailored experiences. I wanted, still, to communicate. I think I wanted also to externalize

another layer of my experience as a personal ameliorative. I wanted to undo an alienation that

I felt in certain experiences. I felt isolated in anxiety in functional daily exchanges, so I set up

a forced, tight arrangement of chairs to simulate an exaggerated account of my experience.

I began, soon after, to use the methods of social intervention to alter, combat or protest

behaviors or conventions that I objected to, either on the grounds of discomfort or ethical

grounds. I picked, from the very beginning, people’s polite avoidance of others, and barring

that, their polite avoidance of depth as my primary focus of antagonism or opposition. In a

project called Benign Solicitation, I sent text messages to strangers that contained only “<3” for

months, to varied degrees of hostility and welcomeness. I sent letters to strangers that asked

of them sincere questions and told them things I would write in my journal. I wanted full access

and full disclosure. I wanted people to be more available and more honest.

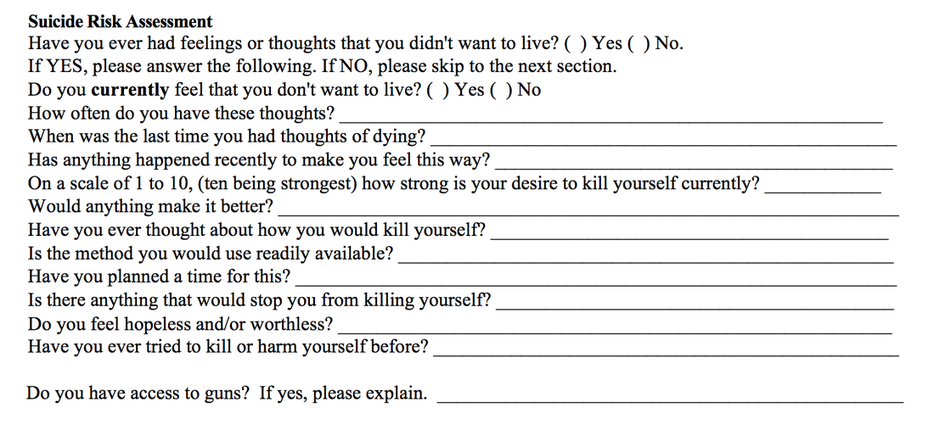

This desire, combined with a recent experience being wrung through the

psychopharmaceutical mill, led me to develop Metaphysician, Heal Thyself. In this project, I

meet with “patients”. These are people who are only limited by interest and exposure to the

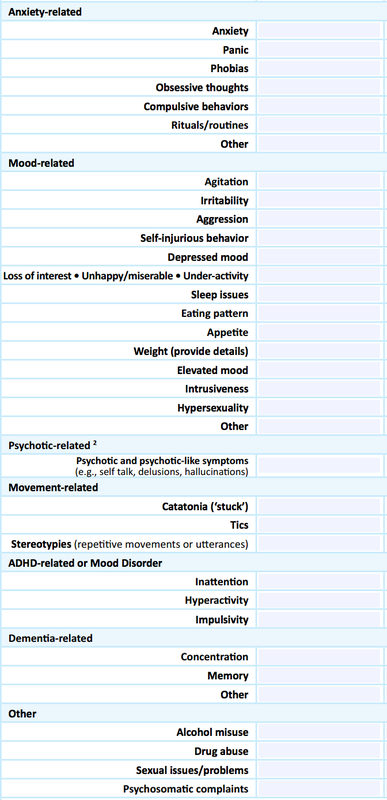

project. We talk in the format of psychotherapy by first answering a series of questions read

from a rubric. I was struck by the dissonance of the form of the questionnaire and the weight

and gravity of the questions on typical psychiatric intake forms. Here is an example pulled from

Lakeview Mental Health in Naples, New York:

3

I was a depressive and disoriented young person, so I have been privy to these

types of evaluation since my early development. My family, fed up with my short fuse and

irrational responses, sent me to psychiatrist. I was diagnosed with depression and prescribed

antidepressants. I started with Zoloft, but made my way through Paxil, Prozac, Lexapro,

Cymbalta, Concerta, and Welbutrin. It is fair to say that I titrated on and off these medications

over twenty times. Each time it causes equal upset and confusion. I lose the ability to see

clearly, to trust my internal dialogue, my dialogical self. This is a deeply troubling phenomenon

since I identify so strongly with my dialogical self. When my dialogical self is misdirected or

delusional, then my entire concept of myself comes into question. In these moments, when

my selfhood is crumbling, I am legally and by defacto obligated to trust and rely upon the

psychiatric institution. This institution is a problematic one on which to rely for a number of

reasons.

Among them, I felt like after minimal and expensive conversation, I was given a

prescription that felt arbitrary. When one didn’t work, we ran down the list. It seemed like I

was given drugs that worked for “people” and not “people like me”. I felt unconsidered in the

process. It felt like an impersonal way to deal with something so personal and vulnerable as my

brain chemistry.

All of the properties of the process were impersonal, as demonstrated in the

intake form above. Putting a number between one and ten to how suicidal one feels is

reductive and embarrassing. The subsequent appeal “Would anything make it better?”

followed by a blank is isolating and strange. It implies sympathy and humanity while negating it

by its form, by asking the patient in writing, and letting them answer on a limited blank line. It

is a lonely, invasive, insensitive form that is written in a human voice, sometimes broken by

medical or survey language, a language whose syntax I am still studying. It’s as though one is

being offered sympathy by a machine. Somehow, the attempt at humanity from something

that wasn’t human, in this case paper, makes one ashamed to experience such human things.

It’s the same shame as when a child makes comments about adult bodies, in that by contrast

and awareness, one is suddenly ashamed of having one. In his essay, “Ideology, Social Control

and the Processing of Social Context in Medical Encounters”, Howard Waitzkin says, “When

doctors convey ideologic notions about desirable behavior, especially as these notions help

shape patients’ roles in work and the family, medical encounters contribute to the broader

hegemonic impact of ideology. In this sense, medicine exerts ideologic effects that parallel

those of such institutions as schools, churches, and the mass media”. The ability of the

language of institutions to impart ideologies is present in the medical institution, and I have

supplanted their language and ideologies for my own.

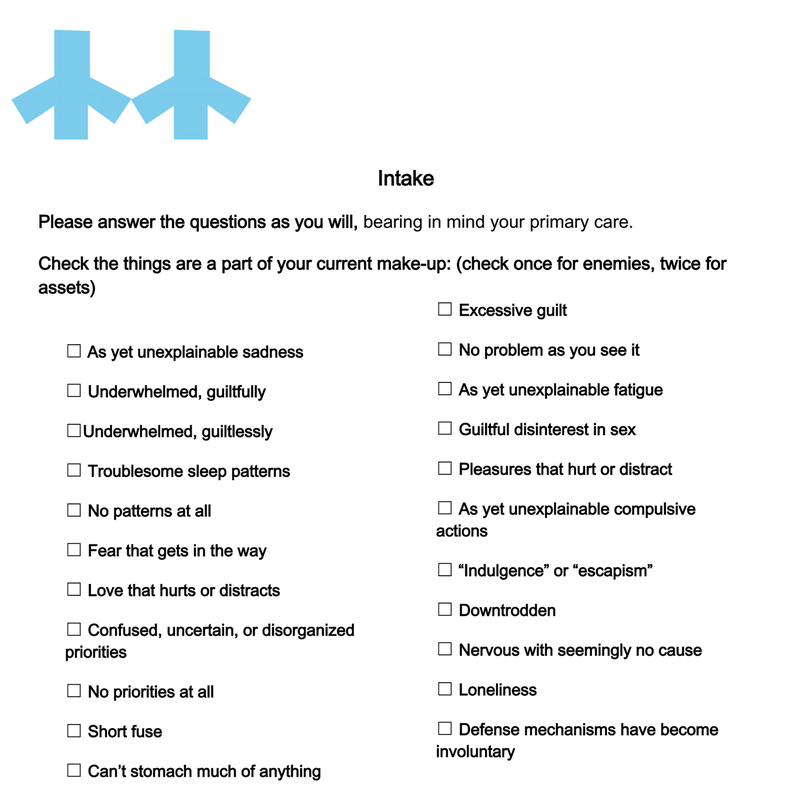

In response, I made my own intake form. My language was more abstract, with the intention

of achieving a less “efficient” vocabulary and a more “emotional” vocabulary. I wanted to

undo the utility of the language, and use language that was new, if less efficient. I thought

of Viktor Shklovsy’s “Art as Technique” in which he says, “Poetic speech is framed speech.

Prose is ordinary speech – economical, easy, proper, the goddess of prose [dea prosae] is a

goddess of the accurate, facile type, of the “direct” expression of a child.” I wanted to frame my

speech, to step out of the “facile type” of “direct” expression that medical forms adopt for their

functioning. I wanted to embed my ideology inside of this framed speech. I worked directly

in opposition to the position Roland Barthes takes on the marriage of ideology and poetry,

when he says in Mythologies, “It seems that this is a difficulty pertaining to our times: there

is as yet only one possible choice, and this choice can bear only on two equally extreme

methods: either to posit a reality which is entirely permeable to history, and ideologize; or,

conversely, to posit a reality which is ultimately impenetrable, irreducible, and, in this case,

poetize. In a word, I do not yet see a synthesis between ideology and poetry (by poetry I

understand, in a very general way, the search for inalienable meaning of things).”

The prescriptions the supplementary forms attempt to find a meeting place of poetry (a

search for meaning, if not inalienable meaning) and ideology. My form follows the “check box”

format of intake modeled like the following taken from the Surrey Place Centre:

May 15, 2014

Immediately, my work was about communicating. It wasn’t beautiful. I wanted,

without knowing, to develop new skills for communicating within my work. When

I gained access to metals and wood, I tried, for the first time, to make interactive

sculpture. The goal was the same: to communicate the ineffable. My tactic, however,

had shifted from showing the ineffable to trying to put the viewer in a position to

experience a metaphorical version of the feeling. For example, to simulate the feeling

of moments of clarity punctuating an otherwise muddled mind, I built a tall enclosure

for the head that allowed sight from small holes in the steel cylinder. I wasn’t satisfied

by these experiments, but my interest in communication was evolving.

When I began as a student at Purchase, I picked up at this metaphorically

communicative phase. I made video work that communicated real thoughts and experiences

through metaphorical actions. For example, I was interested in finding the end of my capacities

in the mode of Marina Abromovic, discovering which would fail first between my body

and my will. An early exploration of this idea was a video called Busy in which I picked an

arbitrary stand in for ‘activity’ by filling a tub with water and punching the surface repeatedly

presumably until I couldn’t. I looked at work like Mel Chin’s SAFEHOUSE (2008-2010) as

examples of metaphorical action that spoke about concrete events. Finally, I took a course that

bridged the gap between lived experience and communication. It was called Social Sculpture,

and in it I learned that one could create real experiences as a form of communication, without a

metaphor or image to mediate.

From there, I began to experiment with putting people in simulated situations to evoke

tailored experiences. I wanted, still, to communicate. I think I wanted also to externalize

another layer of my experience as a personal ameliorative. I wanted to undo an alienation that

I felt in certain experiences. I felt isolated in anxiety in functional daily exchanges, so I set up

a forced, tight arrangement of chairs to simulate an exaggerated account of my experience.

I began, soon after, to use the methods of social intervention to alter, combat or protest

behaviors or conventions that I objected to, either on the grounds of discomfort or ethical

grounds. I picked, from the very beginning, people’s polite avoidance of others, and barring

that, their polite avoidance of depth as my primary focus of antagonism or opposition. In a

project called Benign Solicitation, I sent text messages to strangers that contained only “<3” for

months, to varied degrees of hostility and welcomeness. I sent letters to strangers that asked

of them sincere questions and told them things I would write in my journal. I wanted full access

and full disclosure. I wanted people to be more available and more honest.

This desire, combined with a recent experience being wrung through the

psychopharmaceutical mill, led me to develop Metaphysician, Heal Thyself. In this project, I

meet with “patients”. These are people who are only limited by interest and exposure to the

project. We talk in the format of psychotherapy by first answering a series of questions read

from a rubric. I was struck by the dissonance of the form of the questionnaire and the weight

and gravity of the questions on typical psychiatric intake forms. Here is an example pulled from

Lakeview Mental Health in Naples, New York:

3

I was a depressive and disoriented young person, so I have been privy to these

types of evaluation since my early development. My family, fed up with my short fuse and

irrational responses, sent me to psychiatrist. I was diagnosed with depression and prescribed

antidepressants. I started with Zoloft, but made my way through Paxil, Prozac, Lexapro,

Cymbalta, Concerta, and Welbutrin. It is fair to say that I titrated on and off these medications

over twenty times. Each time it causes equal upset and confusion. I lose the ability to see

clearly, to trust my internal dialogue, my dialogical self. This is a deeply troubling phenomenon

since I identify so strongly with my dialogical self. When my dialogical self is misdirected or

delusional, then my entire concept of myself comes into question. In these moments, when

my selfhood is crumbling, I am legally and by defacto obligated to trust and rely upon the

psychiatric institution. This institution is a problematic one on which to rely for a number of

reasons.

Among them, I felt like after minimal and expensive conversation, I was given a

prescription that felt arbitrary. When one didn’t work, we ran down the list. It seemed like I

was given drugs that worked for “people” and not “people like me”. I felt unconsidered in the

process. It felt like an impersonal way to deal with something so personal and vulnerable as my

brain chemistry.

All of the properties of the process were impersonal, as demonstrated in the

intake form above. Putting a number between one and ten to how suicidal one feels is

reductive and embarrassing. The subsequent appeal “Would anything make it better?”

followed by a blank is isolating and strange. It implies sympathy and humanity while negating it

by its form, by asking the patient in writing, and letting them answer on a limited blank line. It

is a lonely, invasive, insensitive form that is written in a human voice, sometimes broken by

medical or survey language, a language whose syntax I am still studying. It’s as though one is

being offered sympathy by a machine. Somehow, the attempt at humanity from something

that wasn’t human, in this case paper, makes one ashamed to experience such human things.

It’s the same shame as when a child makes comments about adult bodies, in that by contrast

and awareness, one is suddenly ashamed of having one. In his essay, “Ideology, Social Control

and the Processing of Social Context in Medical Encounters”, Howard Waitzkin says, “When

doctors convey ideologic notions about desirable behavior, especially as these notions help

shape patients’ roles in work and the family, medical encounters contribute to the broader

hegemonic impact of ideology. In this sense, medicine exerts ideologic effects that parallel

those of such institutions as schools, churches, and the mass media”. The ability of the

language of institutions to impart ideologies is present in the medical institution, and I have

supplanted their language and ideologies for my own.

In response, I made my own intake form. My language was more abstract, with the intention

of achieving a less “efficient” vocabulary and a more “emotional” vocabulary. I wanted to

undo the utility of the language, and use language that was new, if less efficient. I thought

of Viktor Shklovsy’s “Art as Technique” in which he says, “Poetic speech is framed speech.

Prose is ordinary speech – economical, easy, proper, the goddess of prose [dea prosae] is a

goddess of the accurate, facile type, of the “direct” expression of a child.” I wanted to frame my

speech, to step out of the “facile type” of “direct” expression that medical forms adopt for their

functioning. I wanted to embed my ideology inside of this framed speech. I worked directly

in opposition to the position Roland Barthes takes on the marriage of ideology and poetry,

when he says in Mythologies, “It seems that this is a difficulty pertaining to our times: there

is as yet only one possible choice, and this choice can bear only on two equally extreme

methods: either to posit a reality which is entirely permeable to history, and ideologize; or,

conversely, to posit a reality which is ultimately impenetrable, irreducible, and, in this case,

poetize. In a word, I do not yet see a synthesis between ideology and poetry (by poetry I

understand, in a very general way, the search for inalienable meaning of things).”

The prescriptions the supplementary forms attempt to find a meeting place of poetry (a

search for meaning, if not inalienable meaning) and ideology. My form follows the “check box”

format of intake modeled like the following taken from the Surrey Place Centre:

My check list renamed these phenomena to make them new. Shklovsky’s ideas of

defamiliarization were of interest in this process. He says of Leo Tolstoy’s “Shame”, that, “Tolstoy

makes the familiar seem strange by not naming the familiar object. He describes an object as if he

were seeing it for the first time, an event as if it were happening for the first time. In describing

something he avoids the accepted names of its parts and instead names corresponding parts

of other objects.” I wanted to let the words speak as if for the first time by using strange terms

to name familiar experiences. For example, irritability became “short fuse”. “Loss of interest”

became either “underwhelmed, guiltfully” or “underwhelmed, guiltlessly”. “Anxiety” became

“nervous with seemingly no cause”. The form also asked guiding questions for the counseling

session that follows. I asked “What isn’t working?” rather than “Reasons for visit.” The first page

of the intake form is as follows:

defamiliarization were of interest in this process. He says of Leo Tolstoy’s “Shame”, that, “Tolstoy

makes the familiar seem strange by not naming the familiar object. He describes an object as if he

were seeing it for the first time, an event as if it were happening for the first time. In describing

something he avoids the accepted names of its parts and instead names corresponding parts

of other objects.” I wanted to let the words speak as if for the first time by using strange terms

to name familiar experiences. For example, irritability became “short fuse”. “Loss of interest”

became either “underwhelmed, guiltfully” or “underwhelmed, guiltlessly”. “Anxiety” became

“nervous with seemingly no cause”. The form also asked guiding questions for the counseling

session that follows. I asked “What isn’t working?” rather than “Reasons for visit.” The first page

of the intake form is as follows:

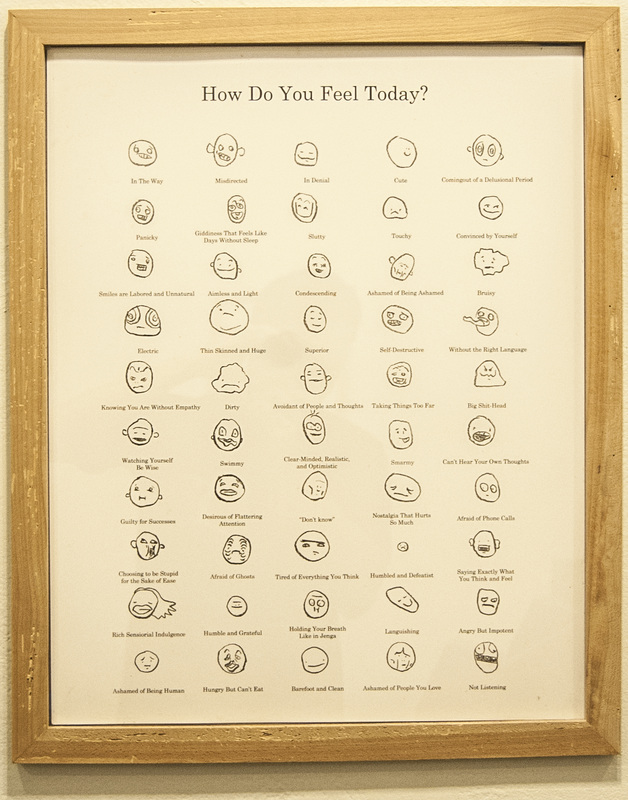

I employ a similar defamiliarization by replacing familiar emotional descriptors in a chart

of emotional identifiers often used in rehabs and clinics. I created a more nuanced vocabulary

of emotions in a standardized format. The dissonance of the gesture had first, a comical

response, and second, an identification, and third, the awareness of the need for a broader

emotional language inside of institutions and everyday language.

The counseling sessions that follow the intake are conversations guided by the checklist

and the questions thereon. I try to pick up a theme in the narrative. I have learned through my

experience with the twelve steps and the Narcotics Anonymous literature to always look for

patterns of behavior and patterns of thinking to diagnose systems of discontent-manufacture. I

use language of industry in describing the processes by which people maintain or manufacture

unhappiness since I believe it is systematic and process based. In the “patient’s” language, I

look for clues about their subjective experience of events in their lives. I look for telling

vocabulary(“he/she/they always…” vs. “I always…”) that indicates the onus of blame. It would

be moot to make a list or a system of things I look for in a conversation since it is much more

natural and intuitive than that. I take all of the skills of close listening and pattern diagnosis I

learned in my sponsor/sponsee relationships in AA and NA and practice them in a new context.

This is my only authority, other than having lived and thought and worried myself. I am good at

both worrying, thinking, feeling, and complicating as well as moving beyond unhelpful patterns

of worrying, thinking, feeling and complicating. I name my project Metaphysician, Heal Thyself

for this reason.

The title comes from a piece of biblical scripture. It is found in Luke 4:23 and reads “And

he said unto them, Ye will surely say unto me this proverb, Physician, heal thyself: whatsoever

we have heard done in Capernaum, do also here in thy country.” I am taking the scripture out

of context and reinterpreting it to mean “do for others what has been done in you.” In this

case, I am the physician. I call myself a Metaphysician instead since I am working with

fundamental nature of reality and being. I have done work in myself of exorcizing harmful

patterns of thought through dialogic and paradigmatic shifts in thinking and action. Capernaum

is myself, and my country is my community. In this interpretation, the passage would read,

“You would surely tell me this, Metaphysician, Heal Thyself: whatsoever we have heard you

have done for yourself, do so also to those around you.” I, as a recovering addict, have a luxury

others lack. I have a guide for growth and change, and a sponsor with whom to struggle. A

sponsor is only qualified by their own similar experience. That is what I am offering to my

“patients”. I am turning this gift around to others who didn’t have to earn it through drug or

alcohol addiction. The biblical reference is a nod toward the faith required of the participants

in order to partake of the process. I ask for faith in words, faith in placebo, faith in me, faith in

a “non-scientific” process. While the conversations between myself and the “patient” are the

most productive, rich, and intimate part of the project for me, there are steps that follow.

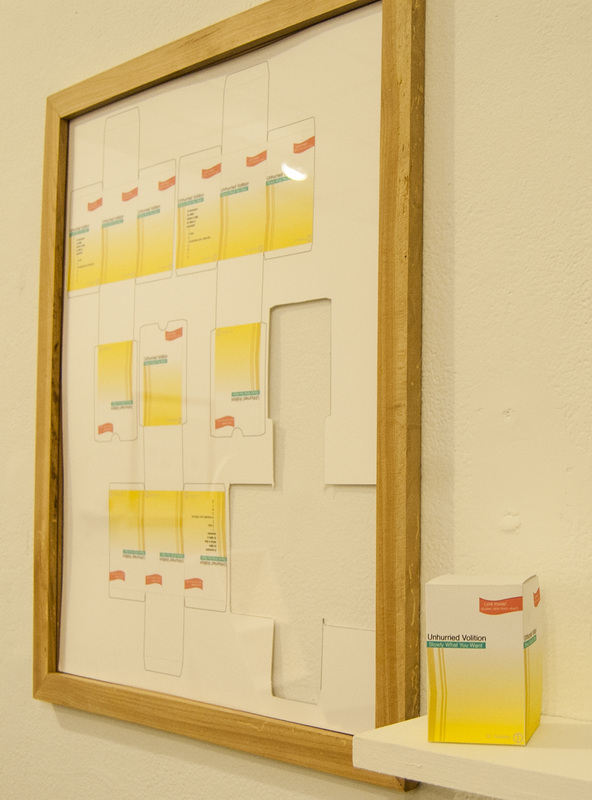

After the sessions, I sit with the notes and recordings from the conversation, and I try to

distill a metaphysical hiccup, conflict, or inconsistency in my “patient’s” thinking. Once

attained, I try to oppose it with a string of words. Again, I employ Shklovsky’s definition of

poetry as fundamentally different in that it is harder to understand than ordinary language. I

attempt to obfuscate some phrases or syntaxes, since, as Aristotle demands, “poetic language

must appear strange and wonderful”. I have offered “Lightness through Likeness” to a

“patient” who, in my estimation, needed to surround herself with people more akin to herself

in order not to feel like she was constantly struggling to assimilate. I offered “Unhurried

Volition: Slowly What You Want” to someone who, as I saw it, moved quickly and without any

sort of consideration of her direction or desire.

and the questions thereon. I try to pick up a theme in the narrative. I have learned through my

experience with the twelve steps and the Narcotics Anonymous literature to always look for

patterns of behavior and patterns of thinking to diagnose systems of discontent-manufacture. I

use language of industry in describing the processes by which people maintain or manufacture

unhappiness since I believe it is systematic and process based. In the “patient’s” language, I

look for clues about their subjective experience of events in their lives. I look for telling

vocabulary(“he/she/they always…” vs. “I always…”) that indicates the onus of blame. It would

be moot to make a list or a system of things I look for in a conversation since it is much more

natural and intuitive than that. I take all of the skills of close listening and pattern diagnosis I

learned in my sponsor/sponsee relationships in AA and NA and practice them in a new context.

This is my only authority, other than having lived and thought and worried myself. I am good at

both worrying, thinking, feeling, and complicating as well as moving beyond unhelpful patterns

of worrying, thinking, feeling and complicating. I name my project Metaphysician, Heal Thyself

for this reason.

The title comes from a piece of biblical scripture. It is found in Luke 4:23 and reads “And

he said unto them, Ye will surely say unto me this proverb, Physician, heal thyself: whatsoever

we have heard done in Capernaum, do also here in thy country.” I am taking the scripture out

of context and reinterpreting it to mean “do for others what has been done in you.” In this

case, I am the physician. I call myself a Metaphysician instead since I am working with

fundamental nature of reality and being. I have done work in myself of exorcizing harmful

patterns of thought through dialogic and paradigmatic shifts in thinking and action. Capernaum

is myself, and my country is my community. In this interpretation, the passage would read,

“You would surely tell me this, Metaphysician, Heal Thyself: whatsoever we have heard you

have done for yourself, do so also to those around you.” I, as a recovering addict, have a luxury

others lack. I have a guide for growth and change, and a sponsor with whom to struggle. A

sponsor is only qualified by their own similar experience. That is what I am offering to my

“patients”. I am turning this gift around to others who didn’t have to earn it through drug or

alcohol addiction. The biblical reference is a nod toward the faith required of the participants

in order to partake of the process. I ask for faith in words, faith in placebo, faith in me, faith in

a “non-scientific” process. While the conversations between myself and the “patient” are the

most productive, rich, and intimate part of the project for me, there are steps that follow.

After the sessions, I sit with the notes and recordings from the conversation, and I try to

distill a metaphysical hiccup, conflict, or inconsistency in my “patient’s” thinking. Once

attained, I try to oppose it with a string of words. Again, I employ Shklovsky’s definition of

poetry as fundamentally different in that it is harder to understand than ordinary language. I

attempt to obfuscate some phrases or syntaxes, since, as Aristotle demands, “poetic language

must appear strange and wonderful”. I have offered “Lightness through Likeness” to a

“patient” who, in my estimation, needed to surround herself with people more akin to herself

in order not to feel like she was constantly struggling to assimilate. I offered “Unhurried

Volition: Slowly What You Want” to someone who, as I saw it, moved quickly and without any

sort of consideration of her direction or desire.

I obfuscate in order to slow down the process of digestion, meaning the phrase will stick

with the person for longer than if it were direct. In the time that the person is forced to puzzle

over the prescription, the phrase becomes a meditation as well as a medication. Often, the

thinking required to untangle or interpret their prescription is a part of the process, since many

people aren’t as intellectually engaged as I would have them be. This is where my “evangelism”

or combatting that with which I disagree in the world remains in tact, which I will address

below.

The process of writing the prescription is a process in finding a balance between

accessibility and poeticism. I want these phrases, as well as the forms they are printed upon, to

be “capable of speaking twice: from their readability and from their unreadability”, as Jaque

Ranciere writes in Malaise dans l’esthétique. The Propeller Group, a cross-disciplinary structure

for creating ambitious art projects founded in 2006, demonstrates the principle of “speaking

twice” in their Television Commercial for Communism, 2011.

with the person for longer than if it were direct. In the time that the person is forced to puzzle

over the prescription, the phrase becomes a meditation as well as a medication. Often, the

thinking required to untangle or interpret their prescription is a part of the process, since many

people aren’t as intellectually engaged as I would have them be. This is where my “evangelism”

or combatting that with which I disagree in the world remains in tact, which I will address

below.

The process of writing the prescription is a process in finding a balance between

accessibility and poeticism. I want these phrases, as well as the forms they are printed upon, to

be “capable of speaking twice: from their readability and from their unreadability”, as Jaque

Ranciere writes in Malaise dans l’esthétique. The Propeller Group, a cross-disciplinary structure

for creating ambitious art projects founded in 2006, demonstrates the principle of “speaking

twice” in their Television Commercial for Communism, 2011.

The ad speaks once through its legibility as a television commercial, strictly following

tropes and aesthetic norms of the genre. It speaks again through the illegibility of the pairing of

its subject, communism, being contained in its form, a quintessentially capitalist structure. I

wanted my pill boxes to speak twice in the same way; once through their legibility as

prescription pharmaceutical packaging, and again through the dissonance of pairing poetics

with the medical form. Allora and Calzadilla, a collaborative duo, were also demonstrative of

this idea of dissonance making meaning in their piece Chalks (1998-2006) in which they scaled

up pieces of chalk to “man size” and placed them in public squares. The ubiquity of the form

matched with the enormity of the scale transformed the pieces from utilitarian objects to

invitations for new uses of the medium. I wanted my pill boxes to transform with dissonance of

form and content, and invite, as did the chalk, a new way of interacting with these

commonplace objects.

Parafiction of the sort that Propeller Group employs was a tool I toyed with and

ultimately rejected in the presentation of this project. I chose to concede my un-realness. I

conceded in the construction of the furniture in my installation. I conceded by not upholstering

the wingback armchair; it wasn’t as it was supposed to be.

tropes and aesthetic norms of the genre. It speaks again through the illegibility of the pairing of

its subject, communism, being contained in its form, a quintessentially capitalist structure. I

wanted my pill boxes to speak twice in the same way; once through their legibility as

prescription pharmaceutical packaging, and again through the dissonance of pairing poetics

with the medical form. Allora and Calzadilla, a collaborative duo, were also demonstrative of

this idea of dissonance making meaning in their piece Chalks (1998-2006) in which they scaled

up pieces of chalk to “man size” and placed them in public squares. The ubiquity of the form

matched with the enormity of the scale transformed the pieces from utilitarian objects to

invitations for new uses of the medium. I wanted my pill boxes to transform with dissonance of

form and content, and invite, as did the chalk, a new way of interacting with these

commonplace objects.

Parafiction of the sort that Propeller Group employs was a tool I toyed with and

ultimately rejected in the presentation of this project. I chose to concede my un-realness. I

conceded in the construction of the furniture in my installation. I conceded by not upholstering

the wingback armchair; it wasn’t as it was supposed to be.

15

It still served its main function (support of weight) but it was other than expected. I

conceded by making the desk, which similarly functioned, but failed in that its drawers were

false. I conceded in the stand, in that it held nothing and therefore didn’t serve its function.

Ultimately I conceded to fiction by situating my project inside of art. I am not certain that

the tension that could have been created by controlling and refusing all concessions but the

context (or even that as well) is not what I’m looking for. I am interested in exploring that

possibility. However, I took pleasure in conceding. It felt in keeping with asking for disclosure

of my participants. The tensions that remained were in the balance between sincerity and

cynicism, sweetness and effectiveness, functionality and hypotheticals. I included audio of the

counseling sessions in each of the furniture pieces as a clue toward sincerity, functionality, and

effectiveness.

I leave the language as open as I can while abiding to my concept also as a

communicative gesture, in which my meaning can be blended or replaced by the interpretation

of the “patient”. For, as Mikhail Bakhtin writes in his The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, “As

a living, socio-ideological concrete thing, as heteroglot opinion, language, for the individual

consciousness, lies on the borderline between oneself and the other... The word in language is

half someone else’s.” The words are half mine, and belong also to the “patient” and to those

who see the products in galleries. The life of the prescription and recordings of some of the

sessions is lived again by those who see the show. The words and meanings transform again in

their reception of them. The prescriptions are also meant to function as a suggestion or

possibility to those who were not involved in the process of making them. This is suggested by

the absent prescription in the framed print.